Impact of Tool Use on Distorted Limb Perception in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome

It's long been known that folks with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) often have strange perceptions of their affected limb – maybe it feels distorted, missing, or even the wrong size. These aren't just odd sensations; these distorted representations of the body and the space immediately surrounding it (that's 'peripersonal space' to you and me) might actually play a role in driving the pain and other symptoms.

In healthy people, these body and spatial maps are pretty flexible. They change, for instance, when we use tools – think about using a broom, it can make your arm feel longer and extend your personal space out to the end of the tool. This flexibility is key. Distortions can happen after something simple like immobilisation (a cast, perhaps), but they usually clear up once movement is back. So, the big question for CRPS was: could the persistent distortions be because the brain struggles to update these maps, effectively preventing normalisation?.

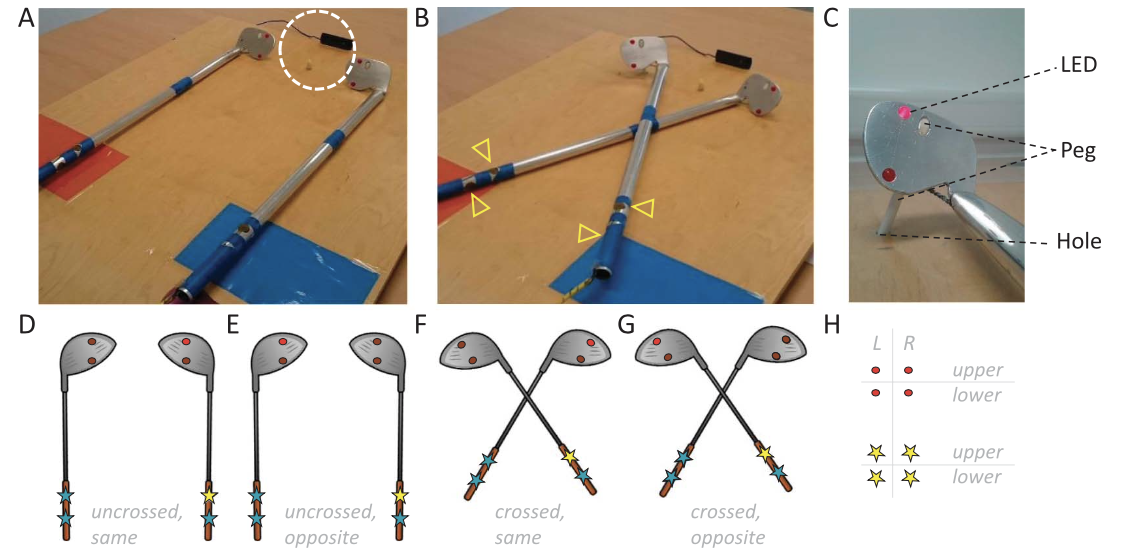

A recent study (Vittersø et al., 2020) decided to test this using tool-use tasks. They had people with CRPS (both upper and lower limb) and pain-free controls use tools and then measured how their body representation changed (using tactile distance judgements on the arm) and how their peripersonal space changed (using a crossmodal task where they had to react to touch on the tool handles while ignoring visual flashes from the tool ends). They initially hypothesised that people with CRPS would be less able to update these representations than controls.

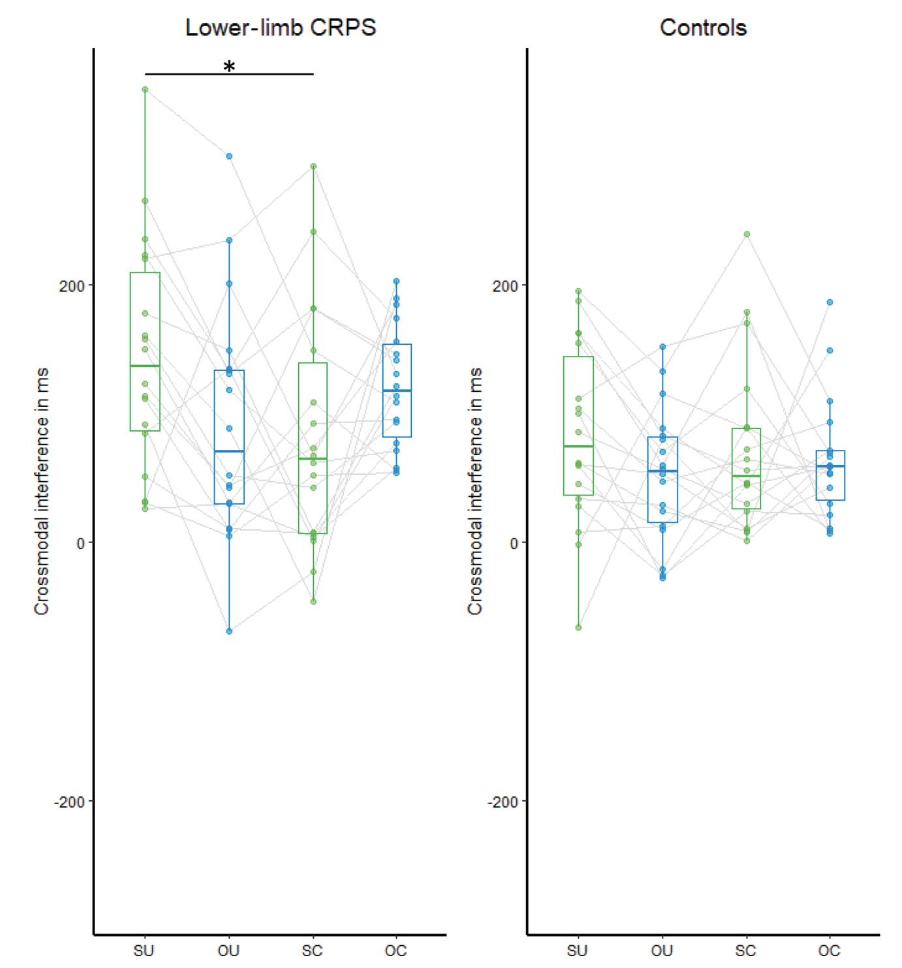

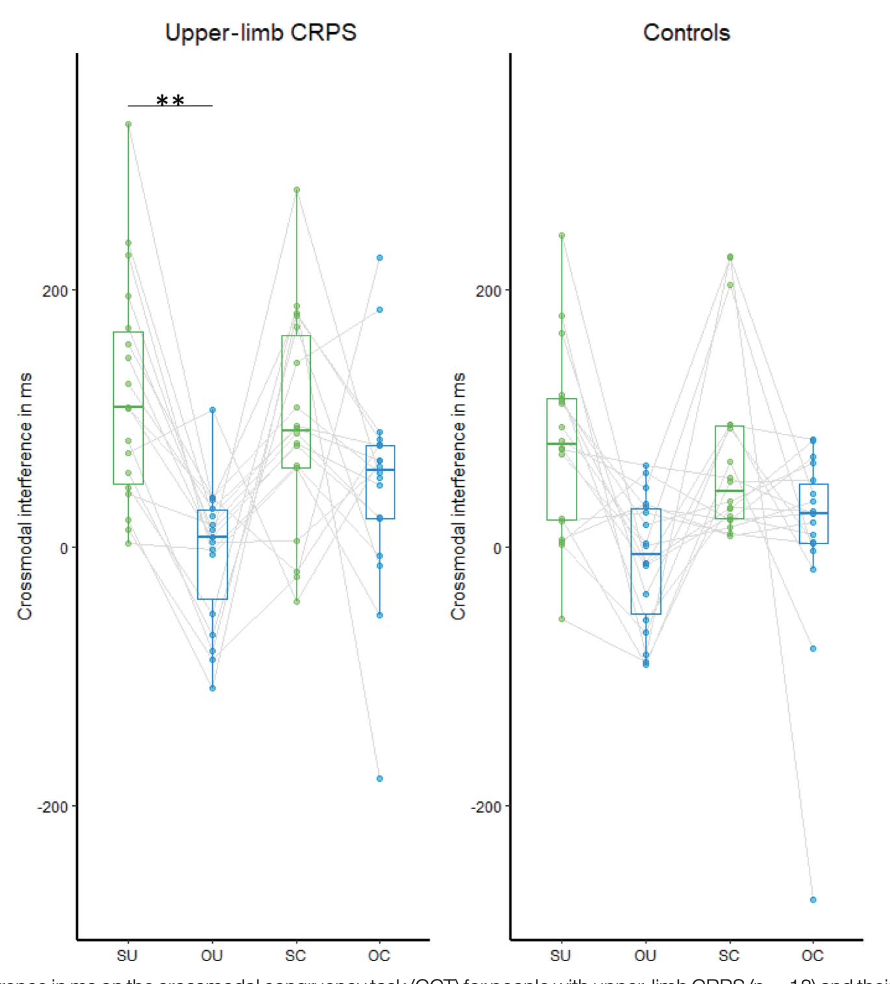

But here's where it gets interesting: they found the opposite! People with CRPS actually showed patterns indicating more pronounced updating of peripersonal space than the controls. For upper-limb CRPS, the affected arm seemed to update its body representation differently compared to the nonaffected arm – possibly a perceived shortening of the affected arm and a perceived lengthening of the nonaffected arm after tool-use. A similar, though non-significant, trend was seen in lower-limb CRPS patients. Curiously, the pain-free controls didn't show the expected updating patterns seen in previous research, which the authors suggest might be due to the sample's age or aspects of the task design. The study also looked at hand temperature asymmetries but didn't find that hand or tool arrangement modulated temperature, which conflicted with some previous reports.

So, what does this mean for clinical practice and rehabilitation? The key takeaway is that these findings suggest enhanced malleability – greater flexibility or changeability – of bodily and spatial representations in CRPS. This points towards alterations in the central mechanisms in the brain. Instead of being "stuck" with distorted maps due to a lack of updating ability, people with CRPS might have maps that are perhaps less stable or reliable.

This idea of less stable representations fits with theories suggesting that a mismatch between the brain's movement (motor) predictions and sensory feedback might drive CRPS pain. If the body map is wobbly, it could introduce 'noise' into the system, increasing the likelihood of this mismatch.

Existing treatments for CRPS, like graded motor imagery and prism adaptation, already target these bodily and spatial representations and seem to help reduce pain and symptoms. The findings from this study provide further evidence that these representations are indeed altered in CRPS, but perhaps in a way that suggests they are more plastic, not less, than previously thought. This altered, potentially hyper-malleable, state could be the target for interventions.

Rehabilitation strategies focusing on normalising these updating processes or enhancing the stability of these representations, possibly by focusing on accurate movement and sensory feedback for both affected and nonaffected limbs, could be explored. The study didn't directly test rehabilitation methods, but its findings on the altered nature of representation updating provide a theoretical underpinning for approaches that aim to refine the brain's maps.

Ultimately, this study adds to the picture of CRPS as a condition involving altered brain processing, showing that the body's representation and the space around it aren't just distorted, but their very ability to change is different in CRPS.